I believe the International Barcode of Life Conference is held every other year. The first conference was held in 2005 and had some 50 attendees. This meeting had over 500 delegates from 68 countries.

A barcode, in most cases, is a segment of DNA that is conserved within a species and variable among species such that each species has an identifying marker. For animals, the mitochondrian cytochrome oxidase I (COI) is typically used and in the plant the chloroplast gene rbcl is often used. However, in plants you may require several genes to nail down a particular species. The method was popularized by Paul Hebert of the University of Guelph. See here for seminal paper.

Our discovery of new species has exploded with DNA barcoding; mostly of very tiny things (< 2 mm). For example, Mark Blaxter of Edinburgh, found a remarkable number of nematodes in a small plot behind one of the university buildings. One thing I learned was that the explosion of discovered species with taxonomic assignment (they haven't been named) has created the need to come up with a term that describes populations that probably are species. They are discovered by running a phylogeny and looking for tight clustering. A cluster is called a barcode index number (BIN) - not very sexy but it allows for easy reference.

Below are three images from the conference from Hebert's talk that I though were particularly thought provoking. The first is the number of pubs over time and the power of barcoding as a new tool pushing science. The second shows an estimate of $250 billion to describe all the species that he estimates to be 8.7 million.

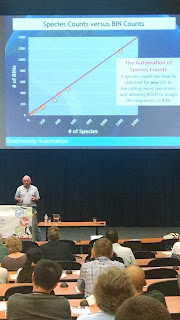

It is going to be a while before I can wrap my head around the BIN thing as a stand in for species but it appears to work. The graph below shows the relationship between BINS and species. There seems to be a 1:1 relationship which suggests that BINS are a good approximation of species.

Dr. Melania Cristescu, of McGill University gave a great talk on invasive species. Her specialty is aquatic ecosystems and gave a nice graphic of shipping density. The result of all these invasions (including terrestrial ecosystems) is biotic homogenization. Species are spread throughout the globe such that the same species are found everywhere.

There were a few food web talks and I found this experiment exceedingly cool. One angiosperm dominates the tundra and Tomas Roslin and his team set out fake sticky flowers to collect the pollinators.

If you think, like I did, that food webs are just hawks that eat mice that eat plants. This bipartite graph shows that they are anything but simple.

I also learned about next generation sequencing (NGS). The younger generation will giggle but I had no idea what NGS was. This is my understanding: NGS allows for the sequencing of multiple genes or gene variants in one run. You can use NGS to do things like identify a number of plants in fecal sample of some herbivore. This is essentially running multiple barcodes at once and it has led to rampant species discovery.

There were great talks, I made great connections and our goal is to present at the next conference. It's a challenge that will be difficult: I have yet to get a single barcode to run. But the uses of barcoding for conservation are numerous and I should learn it.

The best part of the meeting? Barcoded beer: